This post is inspired by a lecture recently given by Barbara Nicolosi titled "

Why Hollywood Matters" in which she discusses the problems in modern Christian and Catholic art, especially film, and ways to counteract these problems. To put it plainly, if one takes a look at the art, storytelling, and music that is in use in most Christian and Catholic churches and subcultures today, in the words of Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI, "We have to conclude that the people of God are afflicted with the cult of the banal." (quote is taken from P. Benedict XVI's

The Spirit of the Liturgy)

The Catholic Church used to be known as one of the chief patrons of the arts, leading to the creation of some of the most beautiful art and music that the world has ever seen. Nowadays, Catholic/Christian art is something pagans sneer at, and with good reason. Say what you want about Hollywood and the atheists and the pagans, but they appreciate the beautiful and they know it when they see it (and when they don't). Why else is it that beautiful stories like

Brideshead Revisited,

Anna Karenina,

The Lord of the Rings, and

Crime and Punishment are just as admired by pagans as they are by Catholics? Why does the majesty of St. Peter's Basilica continue to take people's breath away, regardless of their nationality or belief?

Maybe Catholics have the message right (hopefully), but if we take a look at the craftsmanship of the majority of recent Catholic/Christian stories, films, music, and art, and compare it to that being produced by the pagans, it's little wonder that people don't take us seriously when it comes to art and storytelling.

So how do we fix this? According to Barbara Nicolosi, here are a few ways to bring beauty back into our lives and into our churches:

1. Learn about art -- learn how to do it. Learn how to evaluate it.

Take a class in sculpting or painting. Go to a poetry workshop. Read books on creative writing. Read the Church documents on sacred music and sacred art, e.g. Pope Pius XII's encyclical

Musica Sacra or St. John Paul II's

Letter to Artists. Take lessons in piano or voice. Read about art history or music history. If you find a composer, writer, or artist that you especially like, find out more about that person! You don't have to become a pro -- unless you discover you do have a talent for something, and with that talent may come responsibility to hone that talent and become an artist!

2. Say "No" to banal art and music. No more lame, cheap, ugly, embarrassing art.

|

| Entrance to the Village of Vetheuil in Winter, Monet. 1879 |

|

| Night Before Christmas, Thomas Kinkade |

This comes from learning how to evaluate art: learning how to distinguish between beauty and cheapness, politics, or propaganda : learning what makes Monet better than Thomas Kinkade, why Maurice Duruflé's Ubi Caritas is more compelling than David Haas' You Are Mine; why Michelangelo's Pietà is more beautiful than the political-agenda-inspired multiracial/multicultural/unisex Our Lady of the Angels' statue outside the Los Angeles Cathedral. Beauty doesn't have an agenda. It is just there; it tells the truth without trying. It isn't forced down your throat. It awakens but it does not violate.

Saying "No" to bad art also means acknowledging that just because something is labelled Catholic/Christian or is made by Catholics/Christians does not necessarily make it good. There are many books, movies, and songs written by Christian artists that circulate with ease in our little subcultures but are an embarrassment in public/pagan circles. We are not going to gain converts by circulating poorly crafted, cheap novels and films in our own churches and friend groups -- this is just talking amongst ourselves. We win converts by going out into the world and infusing our art with our faith, not as propaganda but as truth and beauty that is meant for all people.

3. Figure out whether you are an artist or a praiser, and then do that with commitment.

Being an artist requires two things: talent and hard work. Not everyone has a talent for music or for painting, and that's okay. Just because someone doesn't have a talent for art, it doesn't mean he/she can't appreciate it, or do it for his/her own enjoyment. Does that mean that we should let them decorate our churches or make music for our liturgies? No. Sacred art is not for everyone to make. It requires a lot of talent, and it requires a lot more hard work and dedication.

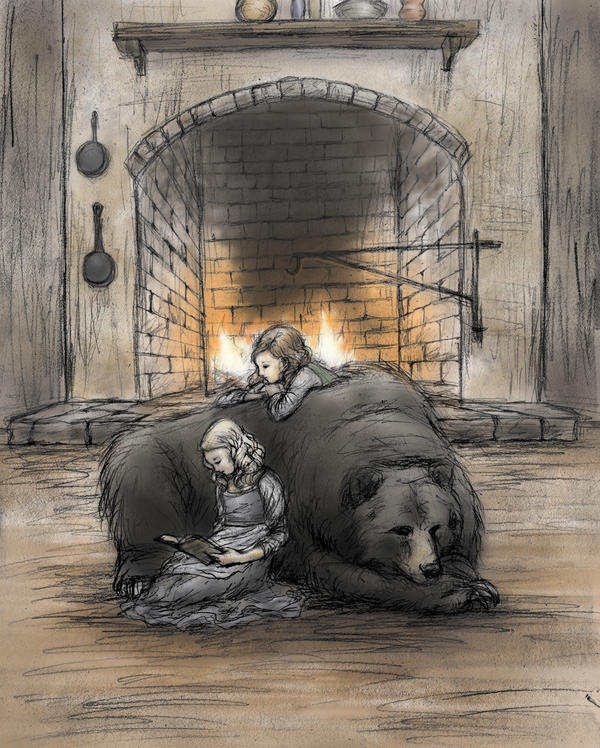

But the good news is that artists need support just as much as the rest of the world needs artists. Artists need us to employ them, to challenge them, and to give them commissions. Not only do they need help financially, but they also need moral/spiritual support, someone to appreciate their efforts -- their hours of isolation, painting or practicing or both; their obsession with perfecting their art, often resulting in being emotionally and/or pyschologically unstable. They need us to remind them what it means to be human beings that need to eat, sleep, have friends, take care of themselves physically and emotionally, and get outside of their isolation just as much as we need them to remind us what beauty is. Why do we (humanity) need artists? To misquote John Keating from

The Dead Poets' Society, "We make art because we are members of the human race, and the human race is filled with passion. And medicine, law, business, engineering -- these are noble pursuits and necessary to sustain life. But poetry, movies, stories, music, art, romance, love, these are what we stay alive for."

So if you are an artist, make great art. Work hard at honing your craft. Practice, practice, practice, read, study, eat, sleep, make friends, have a life outside of your art, and so forth.

If you are a praiser, learn about art and what distinguishes good art from bad art (not everything is subjective), and then find the good artists and commission them to make something beautiful. Artists need to be embraced by a loving Church that supports them through their issues of borderline addiction, insanity, depression, to name a few. Find these people and support them!

.jpg)

.jpg)