Originally written as a reflection on

Start Making Sense! Musicology Wrestles with Rock by Dr. Susan McClary and Robert Walser.

In this particular article, taken from a compilation of essays on popular music titled

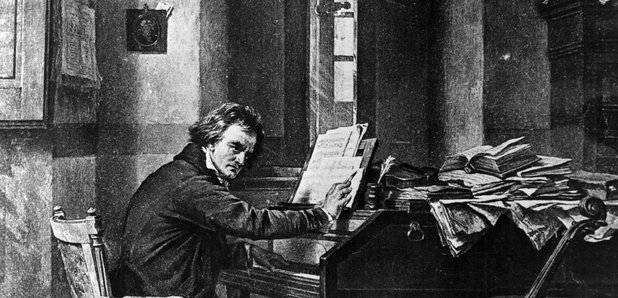

On Record: Rock, Pop, and the Written Word, the authors discuss the difficulties musicologists face when wishing to devote their time and energy to the analysis and interpretation of popular music, from rock to heavy metal to the blues. Popular music is very often at a disadvantage due to the fact that it is traditionally seen as the enemy of classical music. Musicologists who have a genuine interest and appreciation for rock and pop music typically are presented with a unique dilemma in that, since analysis of popular music according to the typical criteria used in classical music is typically far less insightful, they have to look at the music from a different perspective, drawing up their own criteria. the understanding in traditional musicology of the superiority of Beethoven, Strauss, Mozart,

Bach, etc. to popular music has largely been due to the attempts to

judge popular music according to the rules and practices of classical

music. For example, classical music is typically analyzed according to tools such as pitch centers, a method which falls flat when applied to most popular music. This is decidedly unfair, calling to mind a quote from Albert Einstein

which reads, “Everybody is a genius. But if you judge a fish by its

ability to climb a tree, it will live its whole life believing that it

is stupid.” Similarly, if musicologists judge popular music according to its

exploration of pitch centers and tonal goals, it’s going to be found

wanting. Furthermore, an analysis according to pitch centers is only one way to discuss the content and the value of music. Popular musical styles can be just as meaningful and complex as Beethoven, Strauss, and Stravinsky, but in different ways. Musicologists cannot deny the attraction and the emotional impact that this music is

able to evoke, whether it is Frank Sinatra, Michael Jackson, the Beatles, Coldplay,

or heavy metal.

|

| Down the Abbey Road, The Beatles |

McClary and Walser say that this is one of the central aspects of popular music : its ability to move the passions in ways that cannot entirely be explained or controlled, a source of frustration and perhaps even fear for musicologists. However, just because they are afraid of what they don’t understand doesn’t mean they should avoid engaging it or discussing it. I find it intriguing that, while both classical music and popular music have the power to illicit an emotional response from its listeners, these emotional responses can come in a variety of forms. Pianist James Rhodes said that he was emotionally knocked to the floor when he first heard Beethoven’s Emperor Concerto at age seven; the second movement was the first piece of classical music that caused him to weep at its beauty. Then we have historical documents of more violent emotional responses: the premiere of Stravinsky’s

Rite of Spring elicited such a violent emotional response that it caused riots in the theater. Similar violent responses also occur in popular music : moshing has become a common response to live performances of hardcore punk and most styles of metal.

|

| Apollo Belvedere/Pythian Apollo |

It is obvious that music has this ability to create this emotional response, but are all emotional responses equal? Are all styles of music equal? If we cannot judge them according to the traditional criteria used in discussing classical music, then what criteria should we use? To answer this question, I think one must return to the musical discussions of the Greeks. In his writings, Plato categorizes music according to two genres which he names Dionysian and Apollonian. Apollo was typically identified as the god of truth and knowledge, whereas Dionysus was the god of wine, ecstasy, and merry making. Plato describes Dionysian music as a style in which reason is forsaken in a type of emotional intoxication. It advocates a type of anarchy, almost animalistic in its reckless abandonment of the intellect for the sake of revelry in one’s own passions. By contrast, reason remains primary in Apollonian music, ordering our emotional response towards a higher end. This should not to be misinterpreted as a controlled environment in which emotional responses are allowed to occur. Rather, Apollonian music is a genre which engages man’s intellectual, sensual, and emotional faculties in their proper hierarchy. In the words of playwright Robert Bolt, “God made the angels to show Him splendor, as He made animals for innocence and plants for their simplicity. But Man He made to serve Him wittily, in the tangle of his mind.” (Taken from Bolt's play

A Man for All Seasons)

|

| Paul Scofield as St. Thomas More, 1966. |

It seems to me that, while all forms of music may have their time and place and are certainly worthy of study and appreciation on multiple levels, not all musical genres are created equal or have the same value. The highest forms are those which engage the human person on rational, sensual, and emotional levels as these levels were intended. In C.S. Lewis’ book

The Abolition of Man, he describes the image of a man with three faculties : the chest, the stomach, and the head. The chest represents the heart, the stomach the appetites, and the head the power of reason. Man fully alive uses all three of these faculties together in their proper ordering. He states that while it is a gross poverty to raise men “without chests,” -- meaning they have been figuratively castrated of emotional responses -- it is equally wrong for them to allow their emotions or their passions to rule their actions. He adds, “No emotion is, in itself, a judgement; in that sense all emotions and sentiments are alogical. But they can be reasonable or unreasonable as they conform to Reason or fail to conform. The heart never takes the place of the head: but it can, and should, obey it.” Just as man fully alive is made possible through the integration of the head, the heart, and the appetites, so great art and great music is created through the integration of the rational, the sensual, and the spiritual.

.jpg)